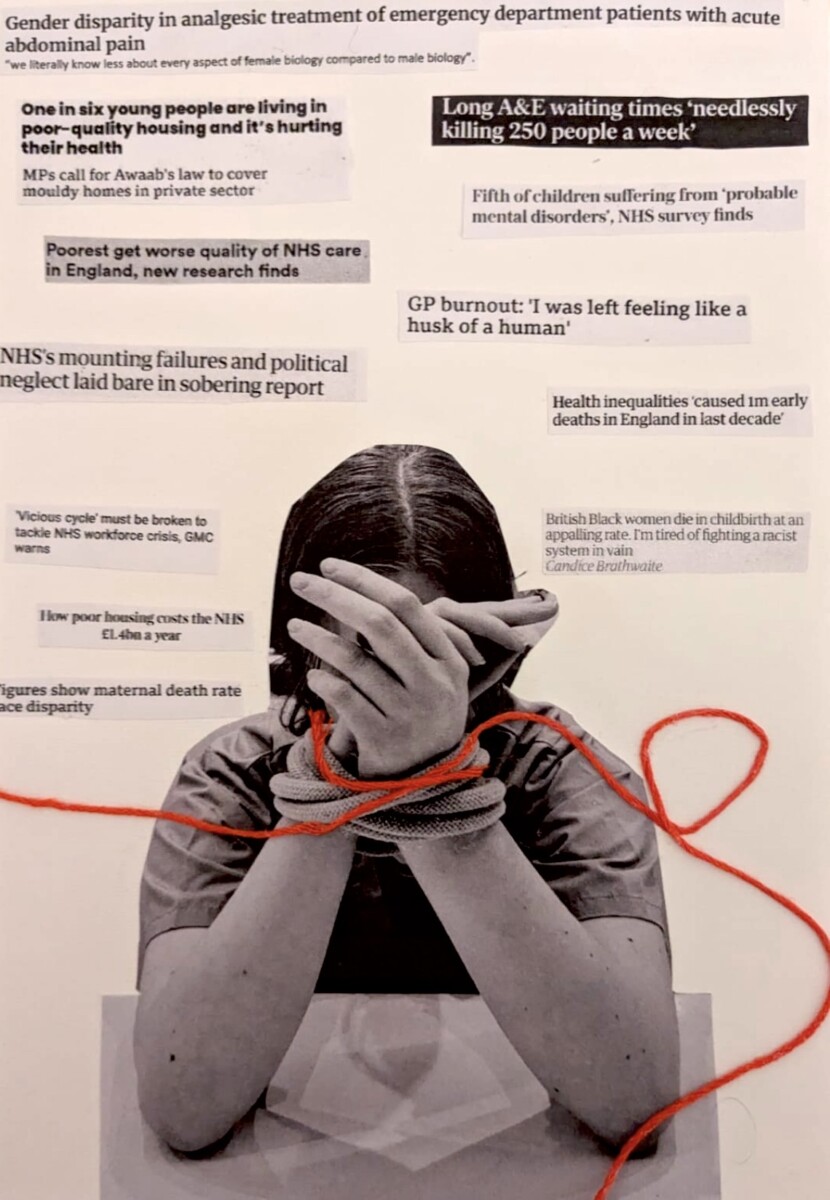

My Hands are Tied

As future doctors we have an inherent desire to heal and make people better, yet throughout my first year of medical school, I have seen first-hand during placements, across hospitals and GPs how much is out of our control.

My art piece shows a doctor whose hands are tied by the various factors that we as individuals cannot change yet have a significant impact on the health and wellbeing of our patients. The headlines surrounding the doctor taken from media articles highlight how the inequality, social and environmental factors I have seen here in Bristol are echoed in hospitals across the country and leave many in our society suffering consequently.

The cost-of-living crisis has left many struggling to make ends meet. It begs the question how we expect our patients to eat healthy food when they rely on foodbanks to feed their family and have little choice on what fills their cupboards each week. How can we help a young child’s respiratory health when they are forced to live in social housing that is damp, mouldy and cold. How can we help patients whose income and employment status already puts them at significantly higher risk of chronic long term physical and mental health problems?

The inequality, prejudice and discrimination experienced by staff and patients motivated by race, gender, social status, medical history or background has catastrophic effects on health both directly and indirectly. Research funding difference, out of date guidelines and archaic hierarchies are just a few roots of inequality, which all result in poorer outcomes for those who need help most. These are systemic failures that have plagued our health service for years, meaning many people are left scared and struggling, unable to get the help they need as we fail to question our own out of date practices, belief and biases.

As clinicians we have to stand back and watch as politicians who have never worked a hospital shift decide how the NHS should be run. We are working in a system that is crumbling around us, surrounded by overworked, underpaid colleagues from every department. As medical students we hear the moans of junior doctors who are placed under huge pressure and expectation, we see the bed-managers frantically trying to place patients in a hospital with inadequate capacity. But you can also feel a huge sense of camaraderie, a sense that we are all in this together and a shared desire to do the best for our patients.

However, when we are doing everything, we can, yet the resources never seem to stretch far enough, it is our patients who must endure the consequences. I have talked to patients who have waited years for a surgery and endured months of pain and discomfort and others who waited hours on a trolly or in an A&E waiting room, just to be seen by a doctor.

Similarly, the increasing demands placed on mental health services mean patients are left to battle with their mental health alone. People are turned away as they are not ‘sick enough’ or don’t meet the criteria to be deserving of help. Our lack of availability means people are forced to reach breaking point before they are seen and tragically this can be too late.

To all these patients and their families all we can say is sorry, there is nothing more we can do in the moment to help. We can offer is a sympathetic ear, maybe a kind smile and sincere apology, but that doesn’t even begin healing the wounds our patients have suffered.

When faced with these systemic, economic, societal and even political problems it can feel like we have failed, despite these all being issues that are beyond our immediate control. It starts to feel that our best is no longer enough.

When presented with the sheer volume out of our control it is easy to despair, yet it really highlights the importance of concentrating on the things we can control:

- We can be compassionate empathetic listeners so our patients can feel safe and validated. They are able to confide in confidence knowing we will do all we can to help.

- We can educate ourselves and our colleagues on disparities and inequalities in healthcare and be aware of our own unconscious biases and actively challenge them each day.

- We can accept and admit ignorance, and we can listen and learn from our patients, colleagues and community to become better able to help and adapt to individual needs.

We can strive to be positive and optimistic in a world that is scary and uncertain.

We will not always be perfect, and the outcome will not always be ideal, but we can support each other through difficult times, accepting what we cannot change and working together to focus on what we can, to create a kinder, more caring and more inclusive health service.

Helen Low, Effective Consulting Year 1, 2023-24

Creative Piece Commended

0 Comments