It was when watching the highly viewed new BBC series ‘Junior Doctors; our lives in their hands’ that something particularly struck me about the doctors of today and those who are currently training. One of the F2 doctors in the programme is what one would medically describe as morbidly obese. Despite being clearly very capable medically one couldn’t help but notice him struggling and panting as he had to run to a cardiac arrest crisis in the hospital as one of the vital members of the cardiac arrest crash team. It was obvious that his physical state hindered him greatly in getting to the patient rapidly and this raised some questions in my mind about how the physical state of some medics, in addition to bad habits such as smoking and alcoholism can impact on their ability as competent and efficient health professionals, in more ways that just the physical.

Firstly, it is known that ‘the medical doctor is one of the most highly respected professionals and patients place a large amount of faith in their doctor’s advice’ and secondly, that ‘doctors’ roles and many would add, responsibility, are exemplar’. This forms part of the basis of a therapeutic relationship that doctors hold with their patients which enables patients to confide in their doctors and subsequently take their advice. A therapeutic relationship requires the patient to be able to in some way identify with the doctor so that there is a mutual understanding of where each is coming from so that a mutual relationship can be obtained in which shared decisions can be made.

In some ways, physicians are expected to lead the fight against disease-causes such as obesity and smoking and serve as role models to the public in order to try and help achieve this. If one takes obesity as an example, it may prove difficult for an overweight doctor to gain a therapeutic relationship and try to convince or encourage an equally overweight patient to go on a diet in order to reduce their risks of heart disease or diabetes, when they clearly do not follow this advice themselves. It would appear to be simply hypocritical and hence break down the mutual understanding between them. There is a human tendency to not respect advice if the person giving it does not follow it themselves and therefore this could pose a huge issue in the counselling of patients. In some ways, obesity is an issue that is more obvious as even though the question of ‘whether the smoking by doctors inhibits any of them from counselling patients against smoking’ is very valid, with smoking it may be less obvious to the patient that their doctor smokes as usually there isn’t much outwards evidence of it other than smell. An argument opposing this hypocritical difficulty is that patients can in fact identify more with doctors who can admit to their own issues of obesity, alcoholism and smoking and share through their own experience. Exposing this more human persona may actually be more encouraging and therapeutic to those patients who struggle with such issues.

In addition to the issue of the doctor-patient relationship with regards to how they present themselves health wise, is also the issue of self-care amongst doctors in such a ‘very, very stressful job’.

The BMA estimated that ‘one in fifteen medics have had a problem with drugs or alcohol at some point in their lifetime’ and in a BMJ study one in 5 male medical students in Europe admits to smoking. However those in positions of authority in the BMA are saying ‘You’ve got levels of denial that make it virtually impossible for an alcoholic doctor to be helped due to the image that doctors are meant to portray’. Many are also saying that perhaps alcohol habits start at medical school where medical societies have ‘the sole purpose of getting their members into a state of oblivion’ and have a ‘supposed “proud history” of drunk medics’. It may raise the question, is it any wonder there is trouble later on? It is an issue, and even though GMC guidelines have improved working hours for doctors, the pattern of little sleep, high levels of stress, studying and little time does drive some to alcohol and cigarettes and the consequent effects of these are not desirable.

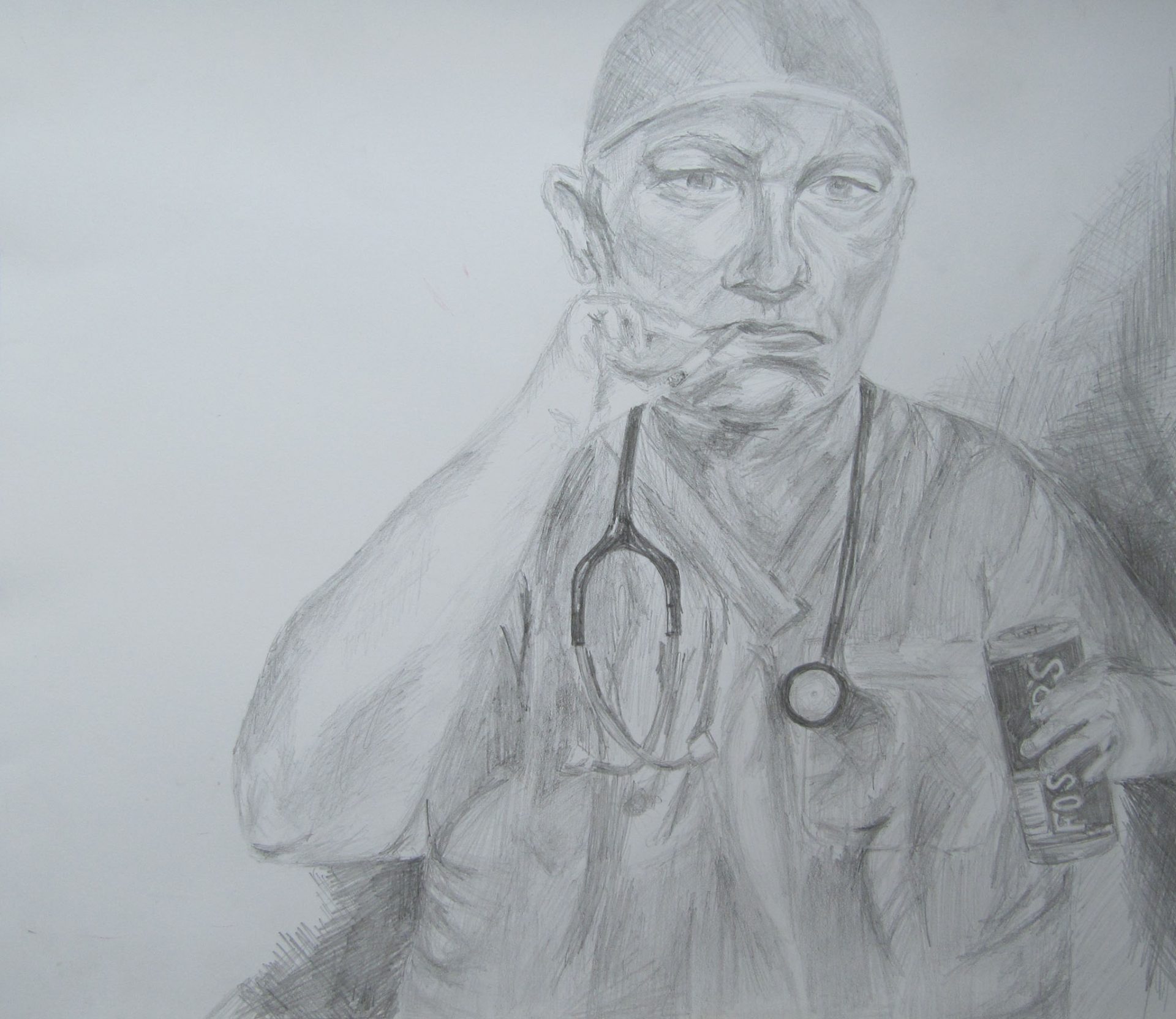

In order to highlight these concerns I have drawn a pencil sketch of a relatively overweight surgeon, cigarette and lager in hand. It is meant to be quite controversial in its paradox of what we would expect of the image of a doctor to look like; a fit and healthy individual looking confident, efficient and alert. I have purposefully emphasised the depressed expression of his face in order to illustrate the negative effects that these habits bring. I chose pencil as my medium so that the greys would complement this dejected appearance and appear striking against the expanse of white on the paper. It is important to realise that although the medical profession are experts in their field of preventing and treating disease and maintaining health, they are only human and far from infallible. There is a tendency for one to think that doctors don’t need advice or help as they have all the answers however medics have the same human temptations and many can be in denial about their situation.

On reflection, making my the art piece reminded me of how much I enjoy and miss art as I continued with it to A-level despite it being perhaps not the most expected subject to take as a prospective medical student. Ironically it showed me that I as a medic have other ways of de-stressing and relaxing other than the reflex of many to go out and drink far beyond the recommended amounts. I do sport which helps motivate me and keep me fit but returning art made me realise I can make time for other pass-times despite having a busy schedule with a lot to fit in the day.

(extract from a Bristol Medical Student WPC assignment)

This sparked quite a debate in my WPC tutorial. Interestingly, all the issues in the description and reflection above were raised, with the main opinions being; ‘Doctors should lead by example’, ‘we can’t expect concordance from patients if we don’t follow the same rules ourselves’ (for things like smoking, drinking, diet etc.) and ‘obesity shouldn’t stop you from being a good doctor if the advice you give is valid and given with good authority’. When I spoke to other students who were non-medics, however, most seemed to hold the opinion that they could not take “orders” from a doctor who doesn’t “practice what they preach” (the main examples being that they wouldn’t listen to an obese doctor who told them they needed to lose weight, or equally stop smoking if they were told to do so by a doctor they caught smoking in the hospital car-park 15 minutes after a consultation. I think it very much rests on the outlook of the patient being treated, and the style in which the doctor in question conducts their consultation.