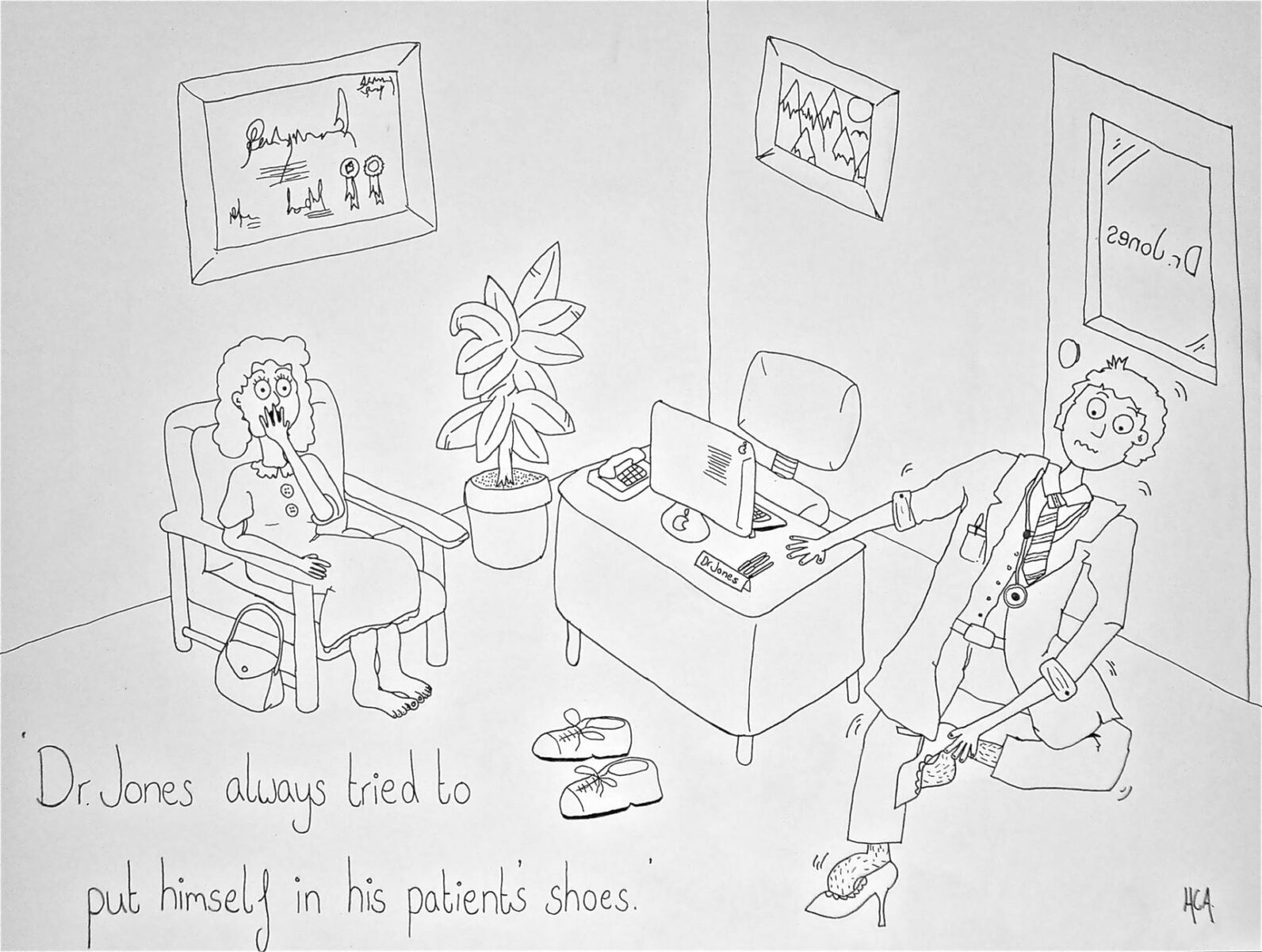

Dr Jones always tried to put himself in his patients shoes

My cartoon depicting ‘Dr Jones’ squeezing into a pair of stilettos plays on the idea of putting oneself into a patient’s shoes. Evidently, demonstrating empathy doesn’t happen in such an outward manner, but alongside the scientific basis of medicine, being empathetic is the core skill in forming an accurate diagnosis. Empathy is defined in the Oxford Medical dictionary as ‘the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts, and experience of another in an objectively explicit manner’[1]. Exploring what medicine itself is, it seems to me a combination of science and emotional awareness are closely intertwined. While for some the idea of problem solving and scientific explanation are what drew them to medicine, for me empathy is far more fulfilling an aspiration.

The medical system is one full of conflicts; the disease with which a patient consults is resultant of the discord present within their body. Successful management of illness seeks to return a persons system to equilibrium. A balance in the welfare of mind and body requires a practitioner to treat both. My cartoon makes light of a phrase applicable to the lives of lay people and doctors alike; to put oneself ‘in another person’s shoes’ is to empathise with them, and for many is this is the route to effective care. For some medical students the idea of squeezing into stilettos isn’t that foreign, however showing true empathy may well be. With the rapid advancement of science, the social side of biomedicine has been left behind. The rising popularity of complimentary and alternative medicine for example, is in my opinion, principally due to the far more empathetic approach granted in that health care setting – ‘what patients valued most were the human factors of listening time and touch-human caring.’[2] Over the past ten years there has been a conscious move towards a more holistic medical approach, with success not only dependent upon the doctor’s clinical knowledge and technical skills, but also on the nature of the social relationship between doctor and patient.

As a medical student, learning to take a medical history is as much about giving a patient time to reveal emotional events as it is reeling off clinical diagnoses. A consultation can become too systematic. Approaching a patient with a clinical tick-box is a coping mechanism against the temporal constraints placed upon practitioners. Diagnoses are sought in such rapid time that emotional involvement doesn’t get a look in. It’s clear that a ten to twelve minute consultation is far from optimum in establishing an empathetic relationship, and as numerical targets in healthcare increase, the system continues to distance itself from the patient. Despite increased emphasis on an approach to doctor-patient interaction in which decision making is shared, the best way for a doctor to demonstrate empathy is to establish a relationship with the patient. With the structure of medical practice undergoing continual changes, the tradition of personal continuity and rapport between an individual general practitioner and patient is becoming less common. Different members of a wider healthcare team increasingly provide care; with nurses, health visitors and counsellors taking on a larger role in the primary care system. In taught communication skills, making eye contact and employing a cheerful greeting are in actual fact far removed from attempting to understand a patient’s thoughts and emotions. Eminent psychiatrist Dr. Helen Riess sites loss of empathy as the intrinsic factor in the failure of health care. A “lack of empathy dehumanizes patients and shifts physicians’ focus from the whole person to target organs and test results.”[3]

The idea of treating a patient’s whole person, rather than simply an organ or a test result, is something that could easily be lost in the first year of medical training. The scientific basis of medical science is laid down so strongly that at some points I have felt like a patient was nowhere in sight. Before the Whole Person Care unit began, what medical school had meant before I arrived felt a little lost. During this assignment I revisited my personal statement for entry to Bristol, clarifying my reasons for doing medicine in the first place. I had written about empathy with reference to work experience; “it was apparent that the skill of the doctor was not only in the problem solving, but in the personal contact; relating to emotional issues and conveying the positives and negatives of the treatment they suggested patients undergo. This combination of scientific knowledge and empathy is what draws me to medicine.”[4] Observing interdepartmental meetings of both gynaecological oncology and chronic respiratory teams left me feeling slightly bemused; patients were described as mere lists of symptoms, resembling a medical problem rather than a person. However emotionally unattached these situations felt, the functional importance was clear. During consultation the communication was more involved, but for a doctor’s own self-preservation it would be too emotionally draining to become attached to each patient. For me, self-awareness, managing emotions and empathy are a vital aspect of who you are as a person as well as a doctor. I was really struck by Doctor McMullen’s conclusion that emotional intelligence is about “the being that lives under the white coat”[5]. A systematic review investigating the therapeutic effect of doctor-patient relationships[6] found that physicians who adopt a warm, friendly and reassuring manner are more effective than those who keep consultations formal and do not offer reassurance.

Whether or not to become emotionally involved in a treatment is not always a conscious choice. For me the most affecting aspect of the Whole Person Care course was the drama portrayed by the thesperados in ‘Cancer Tales’[7]. The emotional narratives of intriguing patients showed their interactions with medical staff in such an open format that it would be impossible to detach oneself from the situation. The consultant oncologist who spoke afterwards mentioned coping mechanisms; for him, doing a good job and being emotionally involved were inseparable.

In the media the portrayal of emotional attachment is often polarized. Drama is generated and feelings stirred by the presentation of doctors in varying lights. I tried to examine some of the recommended films in a manner indicative of the whole person care format, rather than simply as layperson entertainment. In order to create sympathy for the protagonist, the doctors in ‘A Beautiful Mind’[8] and ‘Lorenzo’s Oil’[9] are depicted as emotionally detached and somewhat cold.

The patient’s deterioration in “Lorenzo’s Oil’ is outwardly visible, where in ‘A Beautiful Mind’ John Nash’s schizophrenia arises from underlying emotional issues. His doctor uses brutal physical treatments that lack scientific grounding, to me it seemed that involving himself with Nash and exploring his troubled mind would have reaped more benefit. So profound is the physical degradation of Lorenzo in ‘Lorenzo’s Oil’, the doctor there seems to make a concerted effort to remove himself. The effect of ALD (adrenoleukodystrophy) is so harrowing and individual that the doctor resists personal involvement, instead simply preparing the family for Lorenzo’s death.

To empathise and be emotionally attached or detached is an insoluble dichotomy. Whatever sources one studies, be they literary accounts or first hand consultations, the best treatment is both scientific and emotional. For me, however hard it may be to break bad news or help a family through death, doing so without some degree of attachment would be an injustice.

(extract from a Bristol Medical School WPC assignment)

References

[1] Oxford Medical Dictionary, Oxford University Press 2003; 7th Revised edition.

2 Reilly D, Creative consulting – why aim for it? Student BMJ, volume 9 – page 364, October 2001.

3 Riess D, Empathy in medicine – a neurobiological perspective. JAMA. 2010; 304(14): 1604-1605.4[1] 4 Apperley H, personal statement, 2009.

5 McMullen B, Emotional Intelligence. Student BMJ; 326:S19, February 2003.

6 Di Blasi Z et al. Influence of context effects on health outcomes, a systematic review. The Lancet, Volume 357, Issue 9258, Pages 757 – 762, March 2001.

7 Dunn N, Cancer Tales, performed week 2 WPC 2011.

8 A Beautiful Mind, Film, Directed R Howard, Universal Studios & DreamWorks LLC, 2001.

9 Lorenzo’s Oil, Film, Directed G Miller, Universal Pictures, 1992.

Whole Person Care, Year One, 2011

0 Comments