An Appointment in Samarra

This patient’s death left a bigger impression on me than the handful of others I’ve witnessed. He was an elderly man with end-stage terminal cancer, who passed away during my clinical shift. I stood by the doctor who pronounced him dead, and although I did not know the man, the moment lingered in my mind. Bones wrapped in skin, he looked as though he had been through a lot of suffering; now he was peaceful, asleep. It was a sombre, yet happy, moment.

Reflecting on this, I watched the late Sir Terry Pratchett’s interview “Shaking Hands with Death”. I learned of the old tale “An Appointment in Samarra”, the moral of which is: ‘no matter how far one runs, every man eventually has his appointment with Death.’

I did not realise how strongly I felt about pushing for better end-of-life care. Yes, this man died peacefully, yet I couldn’t help feeling bitter: his death could have been so much better. He could have been in a warm familiar home, surrounded by friends and family. Instead he lay in a cold grey hospital next to five other patients, cared for by strangers who know nothing about his life. The project I wrote years ago on assisted dying had a much greater impact than simply teaching me ethics and law: I saw how ‘good’ one’s death can be, and I now see how woefully short of it we often fall in healthcare.

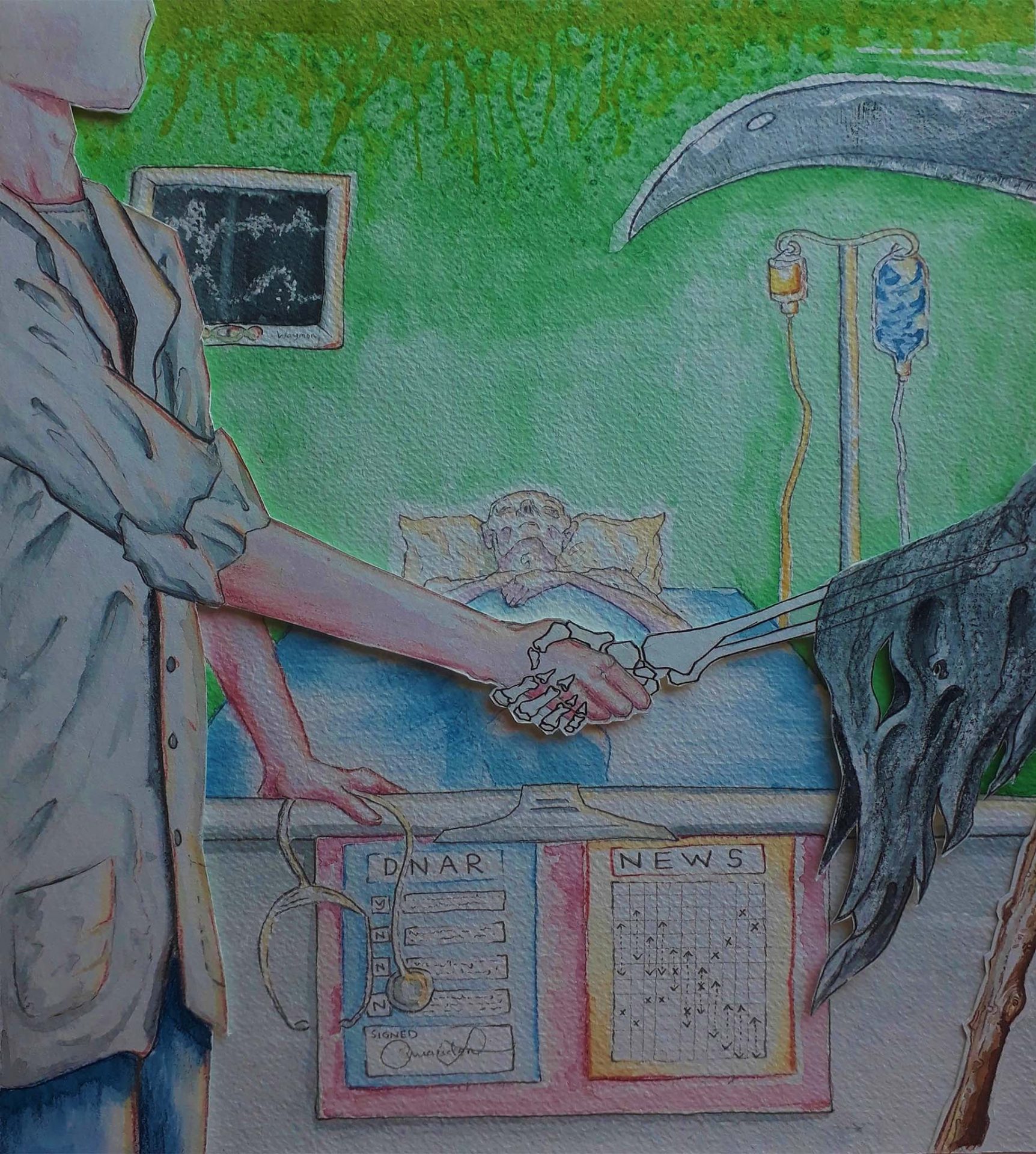

My experience using watercolours helped me visualise techniques which portray these feelings. From Sir Terry Pratchett’s concept of Death as a ‘physical being’, I pictured Death brushing past us as he left the bedside. I imagined the doctor acknowledging Death’s visit – respect for one another, closure – in the form of a handshake.

For the Doctor, I used wet brushstrokes and soft gradients to portray a gentle person, somewhat tired, but alive. In contrast, Death’s stark black-and-white outlined bones give a sense of being cold, hard,’final’.

I used dry-brush strokes for the sleeve for an ethereal, ghostly appearance. Death’s scythe is painted crisp and clean; I did not want to portray him as intimidating or violent, the blade merely the tool of his trade. The doctor’s tool, a stethoscope, is put down, no longer needed. The figures are cut out from a different layer of paper so that the patient (whom I did not know) fades into the background: this intentionally gives the viewer little information about the who the patient is/was. Dilute ,wet, watercolour strokes create this subtle blurred effect. Similarly, the vital signs monitor is obscured and faded – it is not important any more.

Medication in the drip casts an orange glow on the figures, suggesting how healthcare prolonged his life until this point. The chart on the bed depicts medical intervention, improvement, and the man’s eventual decline (heart rate increasing, blood pressure falling), while the ‘Do Not Attempt Resussitation’ form represents our current “end-of-life care pathways”: a lot of paperwork, with a long way to go.

Reflecting on this, I watched the late Sir Terry Pratchett’s interview “Shaking Hands with Death”. I learned of the old tale “An Appointment in Samarra”, the moral of which is: ‘no matter how far one runs, every man eventually has his appointment with Death.’

I did not realise how strongly I felt about pushing for better end-of-life care. Yes, this man died peacefully, yet I couldn’t help feeling bitter: his death could have been so much better. He could have been in a warm familiar home, surrounded by friends and family. Instead he lay in a cold grey hospital next to five other patients, cared for by strangers who know nothing about his life. The project I wrote years ago on assisted dying had a much greater impact than simply teaching me ethics and law: I saw how ‘good’ one’s death can be, and I now see how woefully short of it we often fall in healthcare.

My experience using watercolours helped me visualise techniques which portray these feelings. From Sir Terry Pratchett’s concept of Death as a ‘physical being’, I pictured Death brushing past us as he left the bedside. I imagined the doctor acknowledging Death’s visit – respect for one another, closure – in the form of a handshake.

For the Doctor, I used wet brushstrokes and soft gradients to portray a gentle person, somewhat tired, but alive. In contrast, Death’s stark black-and-white outlined bones give a sense of being cold, hard,’final’.

I used dry-brush strokes for the sleeve for an ethereal, ghostly appearance. Death’s scythe is painted crisp and clean; I did not want to portray him as intimidating or violent, the blade merely the tool of his trade. The doctor’s tool, a stethoscope, is put down, no longer needed. The figures are cut out from a different layer of paper so that the patient (whom I did not know) fades into the background: this intentionally gives the viewer little information about the who the patient is/was. Dilute ,wet, watercolour strokes create this subtle blurred effect. Similarly, the vital signs monitor is obscured and faded – it is not important any more.

Medication in the drip casts an orange glow on the figures, suggesting how healthcare prolonged his life until this point. The chart on the bed depicts medical intervention, improvement, and the man’s eventual decline (heart rate increasing, blood pressure falling), while the ‘Do Not Attempt Resussitation’ form represents our current “end-of-life care pathways”: a lot of paperwork, with a long way to go.

Effective Consulting, Year One, 2017-2018

Creative Piece commended

Creative Piece commended

I found that this artwork captured my attention due to the juxtaposition of the content of the piece with the vivid colours used. The depiction of the doctor shaking hands with the grim reaper deals with the subject matter of patients that do not get better. The grim reaper is not portrayed as an intimidating character but merely someone taking the care of the patient away from the doctor, which highlights that death is an inevitable aspect of healthcare and the sunny disposition of the piece also suggests that beautiful moments can be found in end of life care of patients. Dealing with death is a difficult aspect of a doctor’s career but this piece seems to aim to take the harshness out of the idea of death in a healthcare setting and help physicians to see how there can be ‘good’ deaths.

What I appreciate most about this piece is the effort the artist put into creating symbolism within the piece in the small details that I would never have noticed without the reflections on the piece but are clearly very well thought out. I especially liked the way the artist created two different layers to further allow the background to fade against the very sharp image of death.

What I found thought-provoking from this piece was the idea of mutual respect between the doctor and death. It reflects the inevitable truth that death is the final destination and medicine can only take you so far. Therefore emphasises the importance of the quality of ones final moments, as a doctors duty is not only to prolong a patients life, but also improve the quailty of ones life. Therefore why should the quality of ones death be different, which ties in with the artist’s message.

– Shaking Hands with Death – Accepting that Death is inevitable

– Death portrayed quite eerily but the transition not as a scary process

– Handshake as point of focus, other elements blurred out – sign of respect, Death acknowledging that Doctor has done his part but no more left to do

– Focuses on importance of end-of-life care, just as important as actual treatment, accepting when it is time to stop and just allow a peaceful transition

– Darker green on top but no stark colors standing out surrounding the patient – calming

Artist here – hi all! Thanks so much for your thoughtful and kind comments. It’s so great to hear the different ways the piece engaged each of you. I can feel you really grappling with the core theme, as well as taking it further with ideas I hadn’t even considered. I hope it helps to frame your experiences with end-of-life care as you become doctors 🙂