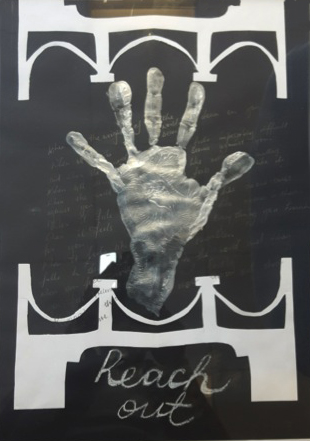

Reach Out

The role requires me to support the social, personal and academic development of students whilst ensuring security, safety and welfare in my halls of residence. In this time, I have come across several cases that have required my pastoral assistance and guidance to students affected.

Working a part of a well-integrated team in this role has not only enhanced my interpersonal, professional and leadership skills but it has also highlighted that despite my ability to work under pressure and respond positively to challenges, I also require the ability to build resilience and its importance alongside self-reflection for self-care. The ability to reflect, and openly discuss and address my mistakes is one that has come through self-awareness and reflexivity, and acceptance and realism.

At the end of a very busy week with examinations season looming, all residents were clearly in revision mode and the atmosphere in halls was somewhat sombre. My halls are in close proximity to a widely-known suicide spot in the city so I was prepared and expected a situation like this to arise at some point. However, I was not prepared for how an unfortunate blend of events from the past would affect how the resident and I would be impacted and how resilience helped me to handle the situation thereby providing better support to the resident.

Although there was no direct casuality, this resident had clearly been affected by events they had just witnessed and how they helped try to save someone. Having run all the way back to their residence the grief-stricken and clearly stressed resident knocked loudly on my door. After sitting down to discuss the events, I was able to recognise my limits and realised that I needed some support from my senior colleagues. It was established that the resident had had a relatable previous experience and held guilt that they had not been able to save their own friend when they took their own life. They had not fully dealt with their friend’s death and blamed themselves for not being fully supportive to their friend.

Despite having confidence in my own resilience and my awareness of my ability to cope well under great stress, I found this situation incredibly challenging. Perhaps the pressure of examinations preparations or the apparent weight of the resident’s previous emotional burden and how it had obviously triggered an elevated emotional reaction impacted and affected my reaction to their case. The intensity or perhaps the timing of a certain event and how past experiences may impact on one’s resolve and strength to cope became very apparent. . Requesting assistance from a senior colleague ensured that I was grounded professionally and ultimately provided resilience through this connectedness.

It was recommended that the resident go for counselling and further reflection augmented my understanding – I could see how overwhelmingly relatable the demands and stresses of a medical degree and medical career would be to this series of events. I was then able to actively engage through their counselling with clear self-demarcation.

To ensure that one copes and prevents a burn out, one has to build resilience. The long hours of work, traumatic experiences, steep learning curves and exams pressure also add to the challenge. Some traumatic experiences can stay with us for a long time, but building resilience ensures that we will give our patients and those in our care the best possible service we can in any circumstances.

0 Comments