Every day we are continually making unconscious decisions to trust our bodies. We trust that our legs will support our weight, that our liver will filter harmful toxins and that our heart will continue to beat just as faithfully as it has since the moment we were born. Disease is a process where our bodies fall short of these expectations. Innumerable risk factors, predispositions and spontaneous intrinsic and extrinsic events integrate into the development of chronic disease in largely unknown ways. A reductionist view of disease would ignore the effects of systemic disease upon a person’s consciousness. Personal and indirect experiences of chronic disease have deepened my understanding of the levels of disease and dualism of mind and body. Substance dualism, as defended by Descartes, suggests that the mind and body are distinct and separate entities (1).

As a medical student, I have a natural interest in pathology, the many pathways and mechanisms by which the human body can fail to fulfil its function correctly is fascinating. The human body is overwhelmingly complicated, often during lectures on a particularly bewildering concept I am amazed that processes such as the homeostatic control of blood glucose functions have evolved to become so flawless. However, just a month after exams I noticed that I was showing symptoms of diabetes mellitus. All the things mentioned in lectures, an insatiable thirst, weight loss and levels of exhaustion that couldn’t be explained by the demands of university life. At first this seemed ridiculous, I had heard all about the hypochondria of the medical student. I fell into the default of convincing myself I was okay and explained the symptoms away. Even when my gp mentioned the possibility of diabetes I shook my head, I had convinced myself that the gallons of water I was drinking was for health benefits, the weight loss was due to a healthy diet and that the blood tests would show the exhaustion was due to some minor deficiency in a vitamin that could be corrected with tablets.

When I found voicemails, texts and emails from my gp telling me to come into the surgery just a few hours after sending my blood off for testing I began to worry; what had they found that was so urgent? When the nurse told me that my blood sugar levels were sky high my first instinct was to laugh. Just a few short weeks ago I had been furiously learning all about the function of insulin and beta islet cells ready for my first medical exam, oblivious to the fact that my own cells were under fire from my immune system. The irony of it seemed comical. I continued to laugh when my blood sugar levels were too high for the blood glucose meter at the GP office to detect, I was amused by the insistence of calling me a taxi instead of the short walk to the hospital, and I enjoyed chatting to the nurses and other patients in the ambulatory care unit and having a patient’s perspective of hospital life.

The next few hours were a blur, and then I found myself alone in a hospital bed, kept awake in the early hours of the morning by the bleeping of monitors and the murmurings of the patients either side of me, attached to drips and my first batch of insulin slowly infusing into my bloodstream. This was the first time I stopped looking at the situation through the eyes of a medical student and really began to realise my situation.

I had never felt so isolated in my own body, the body I had trusted for so long was now failing me. My immune system that had kept me healthy for so long was now attacking my own cells, my protector had become my enemy. I thought about my useless pancreas, about how it had given up on me. I thought about the glycosylation of my cells, the damage to my arteries. I realised the way I consumed food, and my attitude to my own health would have to change, I could not trust my own body to function in the ways I once took for granted. I had to learn how to be my own beta islet cells and how to manually control homeostatic mechanisms fine-tuned by millions of years of evolution. There was no cure, and I realised this disease was going to be with me until the day I died. I felt angry at my body for failing and I felt afraid of how it was going to cause me harm in the future.

After these initial emotions, I have had to adapt to my own diagnosis and restore trust in my body and own ability to cope with treating myself with insulin. I needed to overcome the disconnect I felt with my body and to consciously decide to increase my awareness and self-care to treat the disease effectively. A study published in the journal of developmental and behavioural paediatrics shows that in patients with diabetes, avoidance and wishful thinking were correlated to poor metabolic control and high HbA1c levels (2). To maintain health despite my disease it was important for me to face my disease and not fall into maladaptive coping mechanisms.

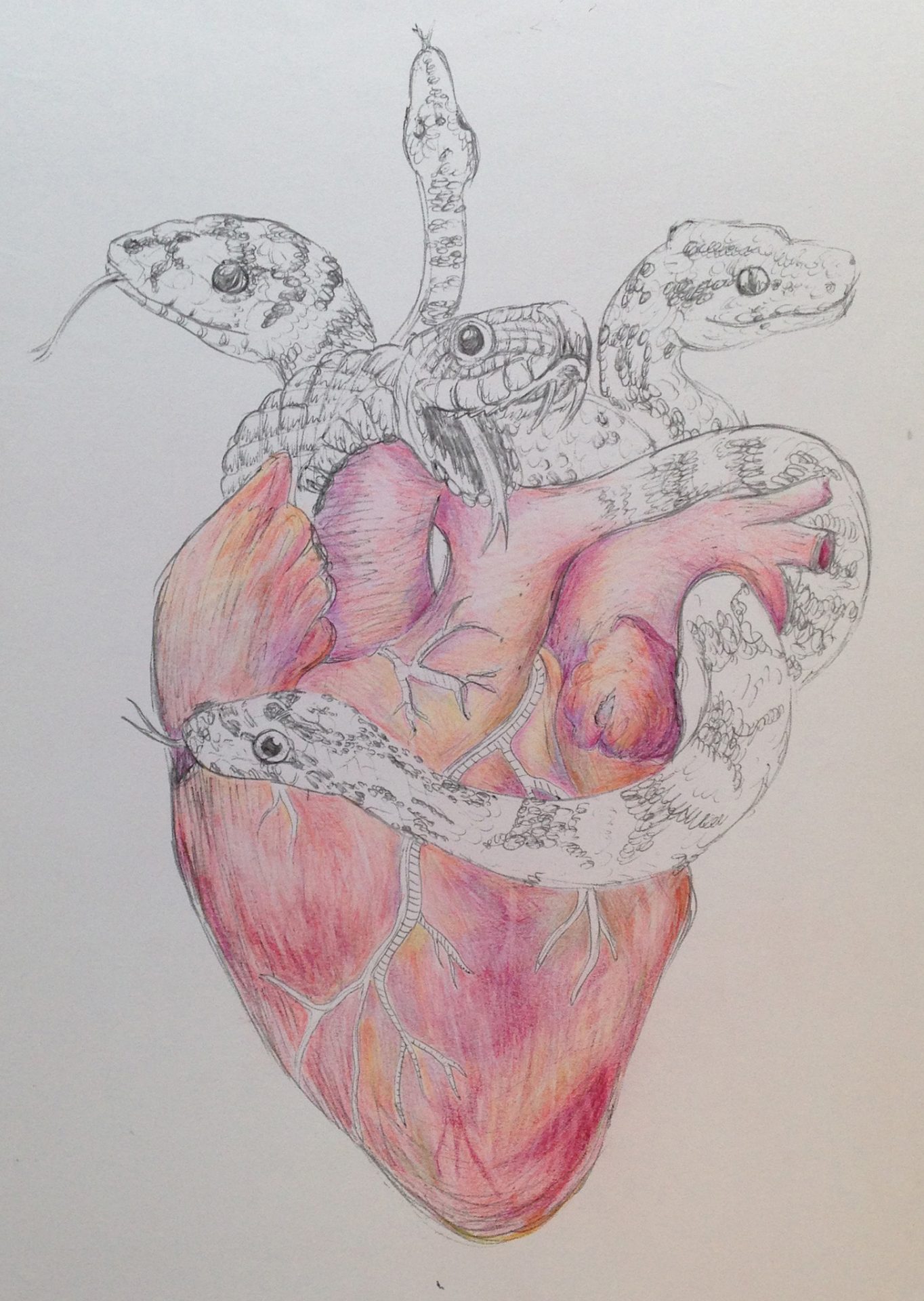

I have explored the relationship between the mind and body in patients with chronic disease in my artwork. The image I have created is a reflection on first hand and vicarious experiences of chronic disease.

The piece shows an isolated heart, erupting from where there should be great vessels are five snakes. My intention is to illustrate how a disease can cause a patient to view their body as something untrustworthy. The snakes symbolise fear, the sensation of something not belonging to the healthy body and the feelings of being deceived by the way the mechanisms designed to protects us cause harm.

The artwork began as a rough sketch with no reference material. I experimented with other mediums but eventually returned to the original biro sketch, as despite not being anatomically correct it captured movement that was missing from other recreations. I photocopied the piece from the sketchbook to make it A3 size and chose to add colour using crayons. The red heart being the only coloured element has the effect of drawing the viewer’s attention to the anatomical drawing from a distance, but as they approach the main draw of the eye changes from the blocked colour to the detail to the snakes. This effect represents the way illness exists at different levels, at a distance the local systemic disease represented by the heart is what the eye immediately focuses on, but up close the cognition and emotional elements represented by the symbolistic and more abstracted snakes show how the whole person is affected by the disease.

I believe I now have a deeper understanding of the mental effects of chronic disease. I appreciate how the worry and anxiety of disease can leave someone feeling disconnected from their own body. In David Mendel’s book “Proper doctoring” he highlights the importance of advising the patient on how to adapt to an illness, not to accept it (3). The act of accepting is passive, it is an important step but it must be followed by adaptation to stimulate personal growth from a diagnosis and to stop feelings of despair, distrust and disconnection from the body. As a doctor, it is important to show compassion and humility to patients that facing the fear and change of a diagnosed chronic disease. Easing this fear and helping a patient to trust their bodies again will help to maintain a patient’s wellbeing so that they can redefine their own version of health despite their disease.

References

1.Robinson H, Stanford encyclopaedia of Philosophy, Available from: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2003/entries/dualism/, [10/04/17]

2.Delamater AM, Kurtz SM, Bubb J, White NH, Santiago JV. Stress and coping in relation to metabolic control of adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Developmental & Behavioural Paediatrics. 1987 Jun 1;8(3):136-40.

3.Mendel D, Proper doctoring, New York, New York Review Books, 2013

Whole Person Care, Year One, 2017

Firstly, thank you for your honesty and courage in sharing your story. It is hard for anyone to face chronic disease but for doctors/medical students to find out that the body, something they know so well, is working against them must be hard to accept. I especially like the idea behind merging the vessels of the heart in to the snakes, showing that our own bodies can turn in to something else without us realising and that can even instill fear in us. The intricacy of the snakes suggests that disease can be so complex, more than just the anatomy and pathology that medical students are taught about, but the emotional and psychological impacts too. The piece as a whole demonstrates the tragedy that is the ability of our bodies to work in opposition to us, and even to strike fear in us, through disease.

Thank you, Martha, for your bravery in sharing your personal experience of chronic disease so it can inspire others. There are many layers to this piece of art which is what made is so captivating for me. The way the heart is drawn isolated from other organs portrays how worry and anxiety of disease can leave someone feeling disconnected from their own body. It also illustrates how the body can be deceiving, symbolised by the snakes, as you trust it to not let you down but its mechanisms can be failing without you realising. Most importantly, this piece reminds us how helpless and trapped we can feel when we develop an illness and to not take our bodies for granted.

Firstly, thank you for sharing your personal experience with being diagnosed and then learning to cope with a chronic illness and learning to trust your body again, it’s something I really connect with, having a chronic illness myself. The idea of trusting your body to work with you rather than against you and having learn to do this is something I can really relate to and myself something I still struggle with to this day despite receiving my own diagnosis over 10yrs ago. The snakes replacing the major vessels coming out the heart is such a clever idea with the symbolism of betrayal that’s often associated with snakes and the feeling of betrayal by your own body experienced by so many chronically ill people. To then expand on it and discuss it from the point of view of a medical student and conflict you felt with how despite knowing the symptoms you still couldn’t bring yourself to accept that this might be diabetes is such an interesting perspective for me since mine is so opposite having had the symptoms and diagnosis before medical school was even a thought and how it actually drove me to want to go to medical school just so I can have a better understanding of how the body is meant to work and why mine doesn’t work the way it should.

Thank you for sharing your personal experience with a chronic disease. I’m sure many people out there will be able to relate to your story and feel less lonely in their struggles because of you. I was initially drawn to the heart, with it being the only thing that was drawn in colour. When I took a closer look, I loved how you drew the coronary arteries on the heart to have scales just like the snakes that encircled it, similar to how a single disease can take up and affect all aspects of a person’s life, not just physically by limiting what we are able to do our daily lives, but also mentally and psychologically as well, inducing fear and anxiety, and making it difficult for us to learn to trust our bodies again.