The Architecture of the Doctor-Patient Relationship

My creative piece was initially inspired by the ability of the GP from my placement to mould her consultation style to fit with the personality of each patient we saw. It was clear that she had an excellent rapport with each individual and was able to switch from cracking jokes about the rugby with a middle aged man to sympathetically asking after the health of an elderly lady’s husband. These very natural and social interactions made the consultation feel less clinical and more friendly and caring, encouraging the patient to be very open. I found it fascinating that with so many different facets to consider when creating a doctor-patient-relationship, it appeared the doctor did so instantly, effortlessly and successfully. Despite the proposed models of doctor-patient-relationship and countless academic psychological studies, the GP was not implementing a scientific method to find the appropriate nature for her consultation. This intuitive and very human side to medicine highlights a blurring of the boundary between the science and art of the profession and is something that I feel is integral to being a successful doctor.

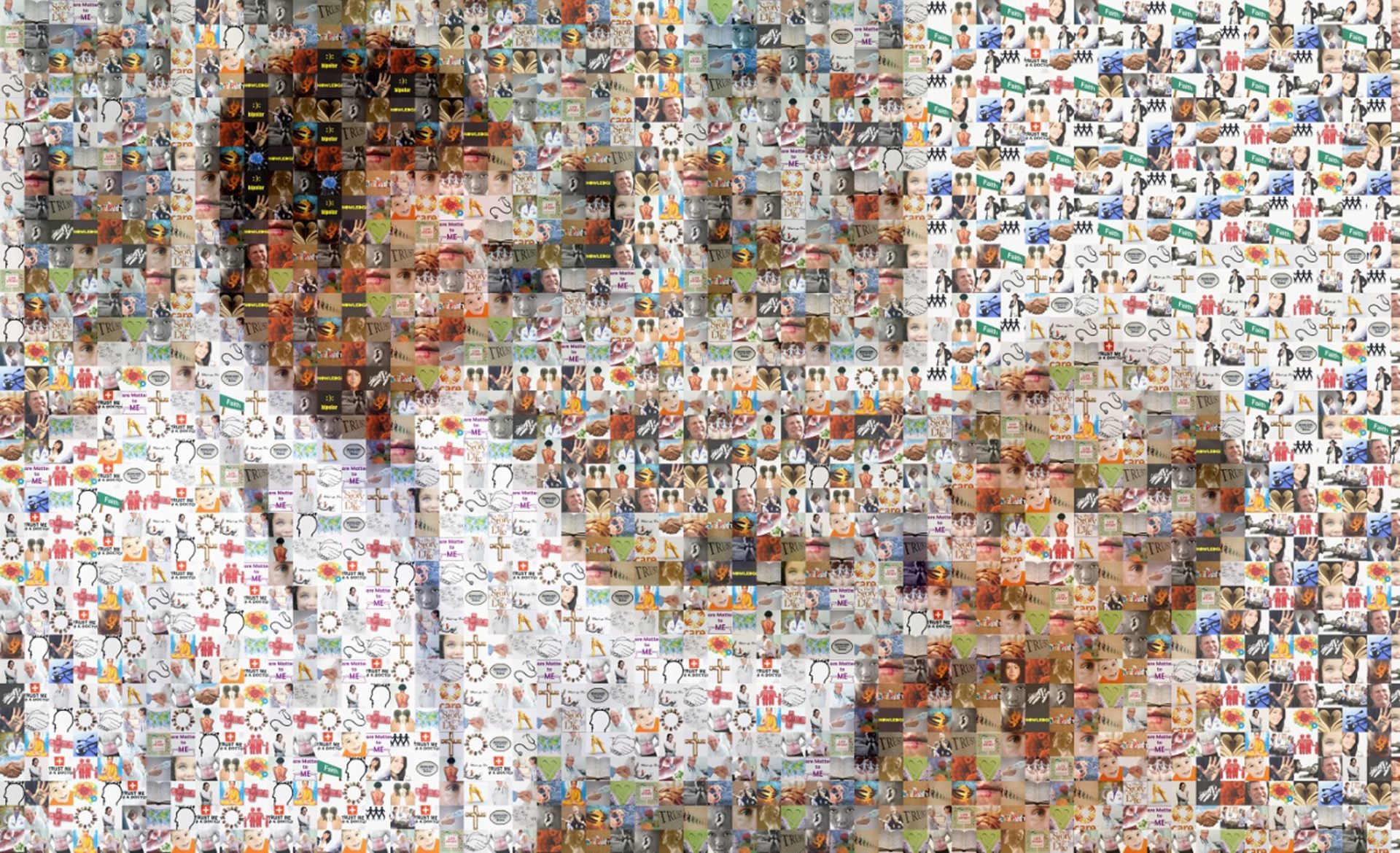

The mosaic shows a doctor with a hand on his patient’s shoulder. They are smiling at each other and I feel this represents a caring and effective doctor-patient-relationship. The mosaic pieces are many smaller pictures of the elements I feel constitute a strong doctor-patient-relationship. Images of the brain and medical equipment symbolize the knowledge and professionalism required by the doctor in order for the patient to show them respect (symbolized by a handshake) and trust (depicted by one person catching another as they fall). Numerous images of caring actions were included to emphasize the important role that doctors have as carers. This also highlights the fact that small actions or even simply listening to the patient can be therapeutic as well as medical intervention. To further illustrate how fundamental listening to a patient’s story is, I used images of ears and books in the mosaic. I also included pictures of shoes and one of adult feet attempting to fit into children’s shoes to represent the importance of empathy in the doctor-patient-relationship. The concept of a mosaic ties in well with the concept of holism and how the function of a relationship cannot be comprehended fully by only considering the parts that create it. What is more important is how the constituents interact and that the strength and effectiveness of the whole is greater than the sum of its component parts. Parallels can also be drawn between the concept of a mosaic and the importance of doctors taking a step back to observe the bigger picture of the patient, rather than concentrating on a certain aspect of a patient’s story. The focus can often be the physical signs and symptoms, which can understandably be the most obvious target for treatment as they are often the patients presenting complaint. However instead of solely treating the symptoms, defining and removing their cause would provide more holistic and effective healthcare.

In my piece, I have included pictorial representations of the many domains in which illness can emerge from within a system. At the physical level, disease can manifest as: molecular dysfunction (represented by a virus invading a healthy cell); local disease (depicted by a cold sore) and whole body disease (illustrated with the AIDS ribbon painted on a persons back). This shows that a small pathology can have a great effect on the whole body which can often be treated or even avoided if it is detected early. However, dysfunction can occur in domains other than those of the tissues. The psychological levels at which illness can lie are: as a functional disease with no physically demonstrable basis (depicted by a metaphoric image of IBS); at an emotional level (portrayed by images of depression, bi-polar disorder and schizophrenia) and at a moral/belief level (represented by various religious images). These images are important to highlight how some aspects of the doctor-patient-relationship are more subtle and some patient problems may need to be explored and cannot be ignored. This point was highlighted to me in one GP consultation where a patient appeared very happy and up-beat however, when asked to fill out a questionnaire on her thoughts and feelings, it was clear she was in fact hiding severe depression. This shows that doctors must analyse the details of the doctor-patient relationship, picking up and acting on any parts that do not fit with the bigger picture. Finally, there are the social levels that disease can affect: familial (exemplified by a shattered cartoon of a family); social (shown by images of domestic violence) and planetary (represented by a globe melting). These pictures indicate that the patients disease can affect other people by putting strain on relationships and families or even contributing to an epidemic. Equally, it could be that factors on the social or psychological levels are causing or compounding the presenting physical complaint – for example, excess stress could lead to an outbreak of a skin rash. Therefore in order to expand our perception of the patients disease, doctors must be sensitive to these emotional, familial and societal issues which may not be immediately obvious. Interestingly, within the first stage of holistic assessment it is necessary to investigate how the various aspects of a situation are patterned and interrelated. This is reflected in the mosaic where the images are repeated a number of times in order to build the larger image. This could emulate two phenomena seen in clinical practice. Firstly, where patients lives can show repeated instances of a problem for example a patient who had a poor relationship with her mother now struggling to bond with her own children. The second interesting pattern is that patients can describe their symptoms or events in their life in a way that echoes their disease or the underlying cause. For example, a patient suffering from alopecia repeatedly using the word loss to describe the death of family members mirrors the disease symptoms – loss of hair. These subtle subconscious references can potentially help to draw out what precisely is distressing the patient and what other levels the disease is having an effect on – perhaps without the patient even being aware.

All these images are arranged in such a way to depict a doctor-patient-relationship and my piece suggests how each facet is vital to consider for each individual patient. The bigger picture of an effective therapeutic alliance between patient and doctor can then be built to uncover and treat the full spectrum of illness. I think it can be very easy to get lost in the medical side of being a doctor and forget about the equally important role as a caring fellow-human. In a busy and sometimes frustrating hospital environment filled with targets and job lists, it is crucial to take a step back and observe how we as doctors are communicating and interacting with our patients on a personal level – with many patients to see, we must ensure that we really do see our patients and not just the illness that they have.

It highlights the importance of the doctor patient relationship as well as its complexity, as well as showing that the patient is as important as the doctor and the fact that the doctor-patient relationship can sometimes be difficult by making the collage slightly blurry. Shows that the underlying aspects of the consultation are the important part rather than the visual aspects. You have to look at the fine details of the piece to be able to appreciate that the doctor patient relationship is an art, which is what makes the piece so poignant and successful.