Dealing with Death – the perspective of both doctor and patient

Some very interesting points are brought up in the play Cancer Tales by Nell Dunn (4). The mother of a patient with terminal cancer really appreciated the honesty of the doctor when he informed her that her was daughter was dying. The use of the word dying was important, removing the possibility of any false hope and helping both mother and daughter come to terms with the situation. I was surprised when the mother described how comforting it was to have a nurse sit with her during her daughter’s last hours. In this situation, I expected the mother to not want to be disturbed but instead she said it was wonderful to have her there, she knew about death and we didn’t. This raises the issue of doctors who don’t have this experience with death, trying to support dying patients and their families.

In a study on how doctors cope with death (1), registrars reported various reactions to the death of a patient such as feelings of shock, self-doubt and personalisation of the tragedy. Strategies for dealing with an emotional response after death included externalisation of the problem, using humour, psychological debriefing, training in breaking bad news and end of life management and support from consultants. Good group dynamics are important, leading to a strong support network. Doctors need to be able execute resilience in order to provide professional support to the family.

It can be difficult for doctors to come to terms with medical intervention failing them and having to accept that there is nothing else they can do. This is one of the themes I tackled in my artwork.

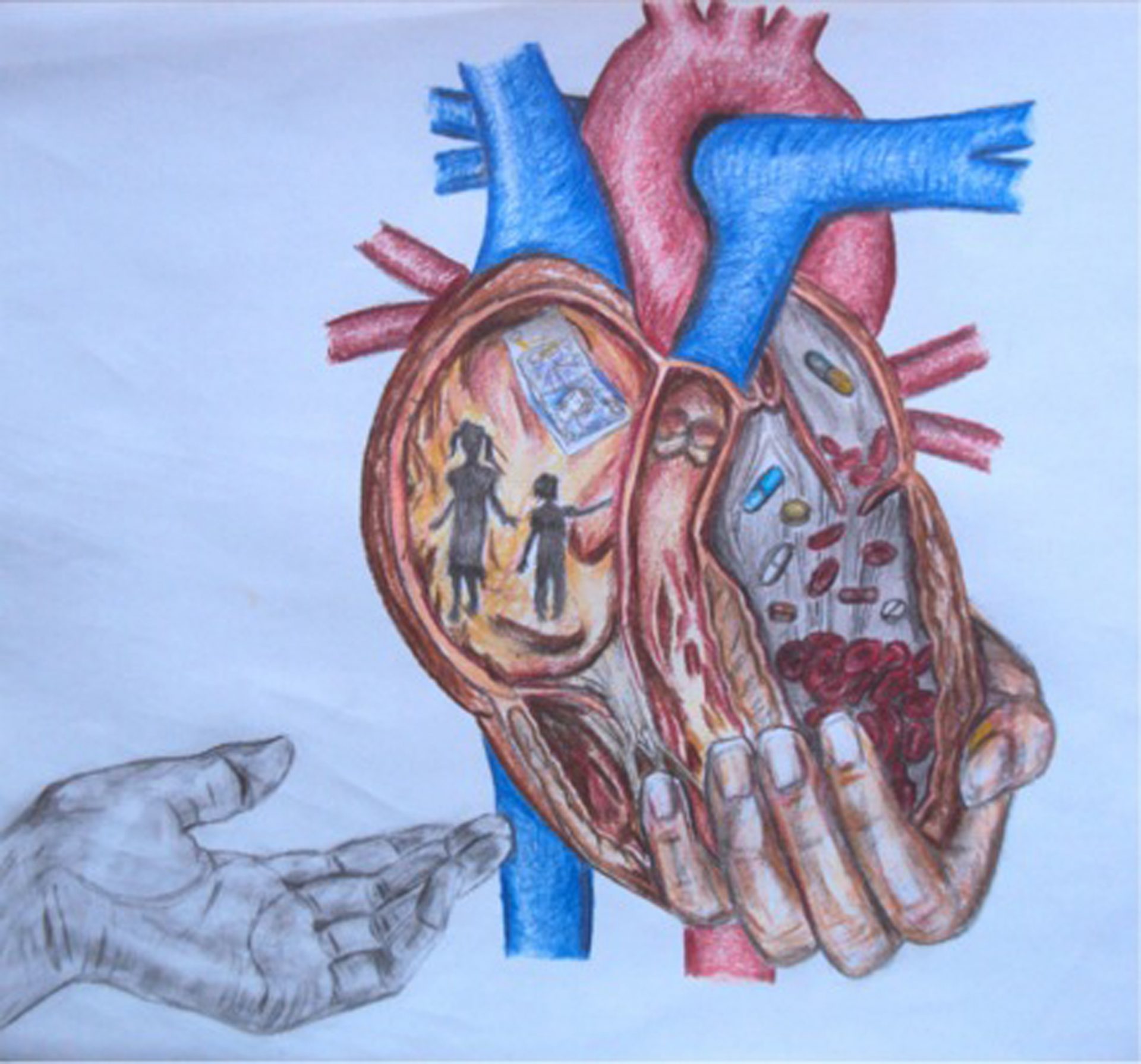

I aimed to accentuate the importance of the arts and creativity in medicine in my creative piece. I want this piece to potentially help doctors come to terms with giving bad news and represent the transition from trying to save the patient, to making them as comfortable as possible as they approach the end of their life (thus showing the power of art in aiding understanding). I have chosen to draw a heart because from a medical point of view, death is the cessation of all vital functions of the body, including heartbeat. I have used the pulmonary and systemic parts of the heart to divide it into the doctor and patient perspectives. The doctor’s side of the heart (left side) is more medicalised with red blood cells trickling through the valve to resemble an hour glass with sands of time, counting down the time the patient has left to live. There are tablets to represent the doctor’s intervention, trying to keep the patient alive. The hand supporting the heart is also to represent the doctor wanting to keep their patient alive as long as possible as they feel this is their role, not wanting to give up on the patient. There is a sense of dehumanisation of the patient, with only medical aspects incorporated.

Meanwhile, in contrast on the patient’s side (right side of heart), I have represented children and finances which are important to the patient before they die. The patient’s hand has let go of the heart and is in greyscale to show that they are ready to give up the fight and leave the world behind, unlike their doctor who wants to prolong their life. Acceptance is defined as the last of five stages of death according to Kubler-Ross (1970) (6) ; this is what the hand letting go symbolises.

Both systemic and pulmonary parts of the heart are integral for survival. Together they provide oxygen for the body to function and neither can work without the other. This demonstrates the idea of a person having different holons/systems which cannot function alone and must rely on each other. The physiological problems are recognised by the doctor, but the psychological and social factors have been ignored.

The drawing certainly does not represent all doctor-patient relationships where death is involved, as each patient is unique with individual circumstances. I just want to highlight how sometimes, doctors can miss what is important to the patient, with whom they have contrasting priorities.

In terms of coping with death, I think that newly qualified doctors should be better prepared and receive more training so that they are comfortable with using the word dying for example and more familiar with the grief process, to better support families of the deceased. As a junior doctor, I am not sure how I will react to death but in order to better prepare myself I intend to discuss any fears with other members of the healthcare team and gain as much understanding as possible in the process of grieving. However each circumstance is unique and people cannot be labelled as being in a particular stage of grief. Training can never fully prepare you for when you encounter the situation in real life.

Having chosen to engage in creative activity I now have even more respect for the role of art in medicine. Ideas which were difficult to express in words were easy to represent in a piece of art and enabled me to reflect further on my initial ideas. From the process of producing my artwork, I have had the chance to think much more deeply about the doctor and patient perspectives of death and realise that there is also a middle ground, where there are common wants and needs after all, the doctor wants what is best for the patient.

I normally lean towards structure, and therefore a normative style, wanting to see patterns in interactions. However now I know how important it is to be a good listener; something I sometimes struggle with because I assume I already know what is going to be said based on past experience. I strive to become an active listener and in future practice, always consider the physical, psychological and social needs of patients.

References:

(1) – F Reynolds. How doctors cope with death. Arch Dis Child 2006; 91:727

(2) – E M Redinbaugh. Doctors’ emotional reactions to recent death of a patient: cross sectional study of hospital doctors. BMJ 2003;327:185

(3) – John Launer. Uniqueness and conformity. Q J Med 2003; 96:615-616

(4) – Dr Trevor Thompson. The Big Ideas in Whole Person Care. Lecture 2: Whole Person Care, Faculty of Medicine, University of Bristol, 2011.

(5) – Graham Scambler (ed.) Sociology as applied to Medicine. Sixth edition. London. Saunders. 2008

(6) – George Norwood. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. [online]. Available from http://www.connect.net/georgen/maslow.htm [accessed 11/03/12]

Whole Person Care, Year One, 2012

I think this drawing excellently highlights how prolonging life isn’t the only aspect of medicine. I enjoyed the contrasts in the different sides of the heart. I think it shows how in delicate situations such as this, it is important for Dr’s to listen to patient’s wishes to help ease the transition. Great work

I think this piece really takes into account what a dying patient may actually be thinking or worrying about and emphasizes the need for doctors to actively listen to them in order to identify these worries. I like how the balance of prolonging life and a comfortable end of life is discussed. Using the two sides of the heart to portray the perspective of the patient against the doctor’s I think is a great thought provoking comparative.

I like how this piece considers death from the perspective of the patient as well as the doctor, in medical school we are all taught that autonomy is the most important ethical consideration, however this so often in not the case when dealing with patients whose death is imminent. This piece deals with opposing positions sensitively and shows it in a positive light, which is very interesting. The contrast of one hand being coloured and the other being black and white is another very subtle way of expressing the differences faced by doctors and patients.

I loved reading the background nature to this piece. I feel that the artist has successfully conveyed the intended message and has brought an aspect of meaning (like the right/left side of the heart and its functions) and figurative meaning (like life, death, finance, children etc). Death comes with serious situations that patients find themselves dealing with, whether it be depression or grief. So I would say this piece portrays a strong message (the emotions associated with death) through the use of contrast and figurative images.

This piece really highlights that the necessity of balancing every-day welling with essential medical care. The comparison with the intricate structure of the heart demonstrates the potential difficulty encountered in doing so but at the same time puts the notion of this balance at the centre of importance.

This is a really powerful piece and it was interesting reading the reflection and the summary to the work. It appreciates how hard it must be for both the Doctor and the patient in such a difficult time. It makes me realise the importance of a Doctor-patient relationship, especially during the time of death. Splitting the heart into two sides is a fantastic way of highlighting this, suggesting that this relationship (as well as the organ) is essential.

I really like how this piece of artwork reflects all aspects of medicine. I think that it shows illness and disease from a patient perspective and a doctors perspective. As well as this it links the doctor patient relationship, emphasising its importance within caring for the patient and how to deliver the bad news of death in the best possible way. Alongside this it shows the clinical aspect of medicine with the drugs and treatment as well as the social and emotional side with the family. I like how it’s linked the heart as a physical organ and its necessity for life with the feeling of love. Overall this piece of art work uses contrasting views to give the overall image of what someone is feeling when dealing with death.

I think this piece deals with the very difficult subject of death. I feel like there is a stigma around death in our society that it is some sort of taboo that cannot be talked about or is avoided. I think this piece highlights the need for people to be more open about death and the struggles new doctors face when dealing with death and breaking news about death to patients.

I think that this drawing is really powerful as it highlights the contrasting roles of a doctor; not just in conventional treatment of disease, but also in social support and the delivery of bad news. This emphasises the importance of a good relationship between a doctor and a patient, especially when it comes to death. In order for a physical heart to function, all elements must be intact and work together. In the same way, it is essential that both conventional treatment and emotional support are balanced in order for a patient to be treated fairly and ethically.

I like how this drawing shows medicine as a whole from two different perspectives: from the perspective of the doctor and the patient. It shows how both the doctor and patient have to work together (like both sides of the heart) for the health system to run smoothly. It also shows how both sides can be interpreting a situation in a completely different way and can be trying to achieve different goals. For me it emphasises the need for good communication throughout the whole of medicine.

I love how this piece of artwork combines my love of anatomy and artwork. It’s eye opening how the same scenario, while difficult for both, is so different and unique. I also like the use of the heart which is crucial to survival, sometimes a doctor may be this essential to a patient moth medically and pastorally

I was struck at the divide between the two sides of the heart and how both their contents are just as important as each other, but so different. The use of the silhouette of the two children as well as the smaller image of money reflects the patient’s views of his/her heart, and what runs through their heart daily. The right of the drawing focuses more on the clinical aspects of medicine and what passes through the heart on a daily basis such as blood and drugs, that inevitably the doctor would play a larger part in. The differences in the hands in their colour around the heart was also interesting, as it is open to interpretation over which hand belongs to the patient and which belongs to the doctor. It could be said that the hand lacking colour could be the doctor, as they play a more passive role in the patients actual feelings, however, the fact that the coloured hand is holding the heart itself could correspond to the doctor’s duty of protecting life and caring for it in the best way they can. The hand lacking colour is drawn in a way that it looks like it is offering a hand to help and support, perhaps indicating the doctor and the comforting role they play in ‘Dealing with Death’.

I really like the way this piece is put together, as it incorporates both the doctor’s view, which is very heavily focused on in medical school, as well as the patient’s own perspective, on which less importance is placed in some cases. The differences in views are really well portrayed through the different colours and focus points. The fact that both perspectives are shown in the same heart shows how both sides are equal and both are needed to deliver the best patient care. It’s a really thoughtful and beautiful piece of art.

I think this picture really captures the conflicting ideas that run through a doctors head when a patient is dying. Should they try their utmost to prolong their patients life or should they ensure that the patient has the best possible quality of life in their final few weeks or months? This is brilliantly represented by showing two different sides of the heart: one filled with drugs and medicine, trying to keep the patient alive and the other full of family members, representing potentially what the patient really values, which is incredibly important when thinking about their end of life care. I really like the addition of the hand in grey scale, letting go of the heart, expressing that despite the doctors trying to keep their heart beating, the patient is ready to die in a calm and comfortable way, not being pumped full of drugs. The hand in grey scale represents, to me, that this concept can apply to anyone as the hand doesn’t have any defining feature, it could be a man or a woman, old or young and from anywhere around the world. I think this is also an important representation as it shows the anatomical structure of the heart, indicating that doctors almost always focus on the ‘science of medicine’ and that when consulting a patient it can become very black and white as to which treatments to give and medicines to prescribe before they move on to the next patient. However the drawings in the right side of the heart show that this patient isn’t some sort of scientific problem for the doctor to solve and then move on, they are a person with family, friends, different hopes and values and none can be treated the same.

I found this piece very intriguing as it highlights the important fact that doctors are also human beings with human emotions. With a busy day-to-day life it can be hard to cope or sort through the feelings we have. It’s also about the patient, it’s about accepting the inevitable end and letting go of the world despite the natural human instinct to survive and keep fighting.

It is a great amount of privilege to be able to physically help them but also mentally relieve them. Patients have come from all different types of backgrounds, with life stories of the good and bad, and all those strings have led them to you. When we form these rapports, it’s more than getting the patient into a comfortable position to tell you how they really feel. It takes a great mental capacity to absorb these feelings and grief. In an unfortunate case, if the patient passes away, how can the doctor deal with the grief? How can they move on knowing all the life stories?